Introduction

Welcome back to this article in which we are going to see more things about number types in Rust. If you haven't seen the previous article where we discussed the basics of number types in Rust, please check that out first.

Note: This article comprises examples that are inspired by Rust in Action book by Tim McNamara.

A little bit about me...

Hi reader 🖐. I am Chiranjeevi Tirunagari and I am a software engineer. You can find more about me on Linkedin and Twitter. Also, subscribe to my youtube channel if you are interested in Rust, DevOps, and tech in general.

Now, let's get started.

Comparing values

We often must compare multiple values and do something accordingly in the code. We check if one value is smaller, greater, equal, or not equal to the other. In Rust, we can compare values if they belong to the same type. That's obvious. That happens in most languages, right? We can't compare an integer with a string in Java. Yeah, but it is much stricter in Rust. We can't compare one integer type ( like a u16 ) with another integer type ( like a u64 ).

For example,

fn main() {

let num1 = 13_u16;

let num2 = 300_u64;

if num1 < num2 {

println!("Went through!");

}

}

If you try to compile this program, it throws an error saying "Types mismatched". But, we can't keep using the same type for all variables. Some variables may require less space when compared to others. We can't just use the bigger type just for the sake of comparison.

But, what we can do is that, we can cast one type to the other just while comparing without affecting the actual type of the variable. So, we can get rid of the error to do what we wanted in the above program by

fn main() {

let num1 = 13_u16;

let num2 = 300_u64;

if (num1 as u64) < num2 {

println!("Went through!");

}

}

If you run it, you should see the "Went through!" output.

If you observe, we typecasted the smaller type into the larger one, not the other way around. That is because we get runtime issues when we try to typecast a larger type to a smaller one. Try to cast a bigger u128 number to the u8 type while printing to see that in action. You will see the change in values. This is because u8 can't accommodate bigger numbers that require u128 and so it wraps around.

Problem with floating-points

Floating points are the numbers that are represented in base 10. But anything that is being stored in computer memory is stored in base 2. This is where the problems arise. This makes the numbers lose precision when dealing with floating points. The following program throws an error which is unexpected generally.

fn main() {

// assert_eq! checks if both arguments are equal

// If not, the program panics (throws runtime error and crashes)

assert_eq!(0.1 + 0.2, 0.3);

}

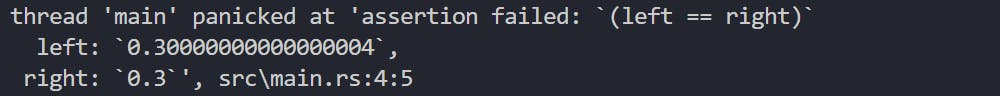

And the error looks like this:

As you can see, it evaluated 0.1 + 0.2 as 0.30000000000000004.

What can we do about this?

We can avoid comparisons between floating points.

Ignore the small difference that we got.

The small difference that we got in the above calculation is called epsilon. And we can write programs in such a way that epsilon is ignored when comparing. The program for the same is below.

fn main() {

let sum: f32 = 0.1 + 0.2;

let expected: f32 = 0.3;

let absolute_difference = (expected - sum).abs();

// assert! panics if the expression inside evaluates to false

assert!(absolute_difference <= f32::EPSILON);

// EPSILON is a constant available for both f32 and f64 types

}

There shouldn't be any error in this as we are accounting for the epsilon now.

Not a Number

Not a Number (NAN) is also a floating point number that doesn't have any value. This usually is resulted when we try to do operations that result in undefined. Examples include taking square root for negative numbers, etc. To see this, let's write a program.

fn main() {

let root = (-56_f32).sqrt(); // sqrt function returns the square root

assert_eq!(root, f32::NAN);

}

This program panics even though both the arguments for assert_eq! are NAN. This is because NAN is not equal to NAN. You can confirm this using the following program.

fn main() {

assert_eq!(f32::NAN, f32::NAN);

}

Even this panics, which confirms our statement that NAN is not equal to NAN. How do we confirm if a result is NAN or not? We have a function called is_nan() for this purpose. Let's change our program to use that function.

fn main() {

let root = (-42.0_f32).sqrt();

assert!(root.is_nan());

}

This program shouldn't panic. We have a function called is_infinity() to deal with infinity cases like dividing with zero, etc. An example of that is below.

fn main() {

let result: f64 = 11.0 / 0.0;

assert!(result.is_infinite());

}

Conclusion

I hope this article helped you understand something that you already don't know.

If you find this read-worthy, please don't forget to like, share your thoughts and share this article with your friends and community because that encourages me a lot. Also, don't forget to connect with me on the socials I mentioned in the intro. Subscribe to my youtube channel as well for similar content if you are a visual learner. Let's meet in the next article, bye-bye 👋 until then.